by Tim Harding

(An edited version of this essay was published in The Skeptic magazine, December 2015, Vol 35 No 4, under the title ‘Bad Medicine’).

One of the distinguishing features of traditional Chinese culture has been the unusually high value placed on rare animal and plant products – the rarer they are, the more valuable they are. This high value applies to both formal dining and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

By definition, endangered species are extremely rare. In western cultures (and increasingly so in modern China) endangered species are more highly valued alive than dead. The demand for rare TCM ingredients has become one of the major threats to the survival of endangered species such as rhinoceroses, tigers, Saiga antelopes, and seahorses.

TCM is a broad range of claimed health treatments sharing common concepts that have been developed in China from traditions more than 2,000 years old. TCM includes various forms of herbal remedies, acupuncture, massage, exercise and dietary practices. It is widely used in China, and also in the West as a variety of so-called ‘alternative medicine’.

Not only is TCM a threat to endangered species, but there is also a dearth of evidence for its efficacy. A Nature editorial has described TCM as ‘fraught with pseudoscience’, and said that the most obvious reason why it hasn’t delivered many cures is that the majority of its treatments have no logical mechanism of action. Worse still, some TCM ingredients have been shown to be dangerously toxic to humans and other mammals.

What is TCM?

It is important to distinguish TCM from mainstream medicine as practiced in China. Most hospitals and clinics in China are run by the government, practising scientific or what we would describe as western medicine. TCM is administered in private clinics, run by practitioners who generally do not have a western medical education. In the past, TCM practitioners learned their trade from their parents (mostly from their fathers); but more recently they have been studying TCM at universities in modern China.

TCM holds that the body’s vital energy (chi or qi) circulates through channels, called meridians, that have branches connected to bodily organs and functions. Concepts of the body and of disease used in TCM reflect its origins in pre-scientific culture, similar to the ‘theory of the four humors’ dating from Hippokrates in ancient Greece. The idea of vital energy or vitalism is similar to that of the ancient Roman surgeon Galen, and which endures in naturopathy and other varieties of western quackery today. These similarities are most likely a coincidence, as there is no historical record of communication between China and ancient Greece or Rome.

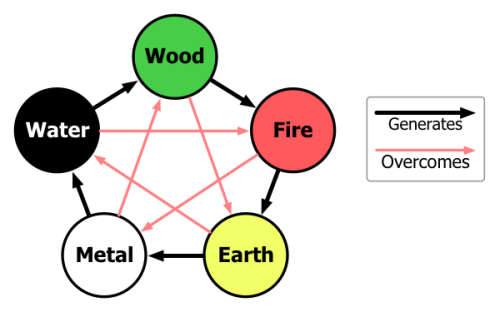

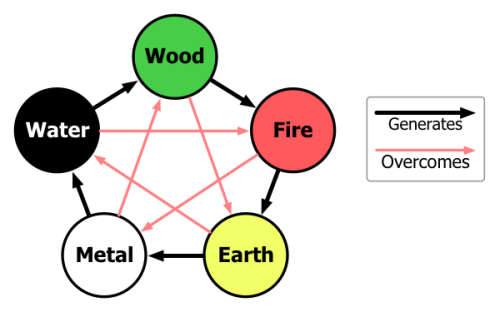

The underlying philosophy of TCM is based on Yinyangism – the combination of the concepts of Yin and Yang with what is known as the Five Elements theory.

Yin and yang are ancient Chinese concepts representing two complementary aspects that every phenomenon in the universe can be divided into, including the human body. Analogies for these aspects are the sun-facing (yang) and the shady (yin) side of a hill, as shown in the iconic Yin and Yang symbol below. In TCM, the upper part of the human body and the back are assigned to yang, while the lower part is believed to have the yin character. Yin and yang characterization also extends to the various body functions and disease symptoms.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Five Elements theory (also known as Five Phases Theory) presumes that all phenomena of the universe and nature can be broken down into five elemental qualities – represented by wood, fire, earth, metal and water. In this way, lines of correspondence can be drawn as shown in the following diagram.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Complex rules apply to the interactions between the Five Elements. These interactions have great influence regarding the TCM model of the body, which places little emphasis on anatomical structures. Instead, TCM is mainly concerned with various functional entities (which regulate digestion, breathing, aging etc.). While health is perceived as harmonious interaction of these entities and the outside world, disease is interpreted as a disharmony in such interactions. TCM diagnosis aims to link disease symptoms to patterns of underlying disharmony, for example by measuring the pulse, inspecting the tongue, skin, and eyes, and examining at the eating and sleeping habits of the patient.

Traditional Chinese herbal remedies account for the majority of treatments in TCM. They also comprises the aspects of TCM that are of most threat to endangered species. However, the term ‘herbal remedy’ is a bit misleading in the sense that, while plant elements are by far the most commonly used substances, animal and mineral products are also utilised.

History of TCM

Herbal remedies have been used in China for more than 2000 years. Among the earliest literature are lists of prescriptions for specific ailments, exemplified by the manuscript Recipes for 52 Ailments, found in tombs sealed in 168 BC at Mawangdui, an archaeological site located at Changsha in China’s Hunan province.

The doctrines of TCM are rooted in ancient books such as the Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon from first century BCE and the Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders and Miscellaneous Illnesses from the third century CE.

Written in the form of dialogues between the legendary Yellow Emperor and his ministers, the Inner Canon was one of the first books in which the doctrines of Yinyang and the Five Elements were synthesised into the TCM model of the body. The subsequent Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders focused on herbal remedies rather than acupuncture, and was the first medical work to integrate Yinyang and the Five Elements with herbalism.

Succeeding generations augmented these works, as in the Treatise on the Nature of Medicinal Herbs, a 7th-century CE Tang Dynasty treatise on herbal medicine. Arguably the most important of these later works is the Compendium of Materia Medica compiled during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644CE) which is still used in TCM today for consultation and reference.

In 1950, Chairman Mao Zedong made a speech in support of TCM which was influenced by political expediency, because of a shortage of science-based doctors and also for national unification purposes. However, Zedong did not personally believe in TCM or use it.

Efficacy and safety

Scientific investigation has found no physiological or histological evidence for traditional Chinese concepts such as qi, meridians, or acupuncture points. The effectiveness of Chinese herbal medicine remains poorly researched and documented. For most products, efficacy and toxicity testing are based on traditional knowledge rather than laboratory analysis. Pharmaceutical research has explored the potential for creating new drugs from traditional remedies, with few successful results.

A review of cost-effectiveness research for TCM found that studies had low levels of evidence, but so far have not shown beneficial outcomes. A 2012 Cochrane review found no difference in decreased mortality when Chinese herbs were used alongside Western medicine versus Western medicine exclusively.

Dr. Stephen Barrett of Quackwatch writes: ‘TCM theory and practice are not based upon the body of knowledge related to health, disease, and health care that has been widely accepted by the scientific community. TCM practitioners disagree among themselves about how to diagnose patients and which treatments should go with which diagnoses. Even if they could agree, the TCM theories are so nebulous that no amount of scientific study will enable TCM to offer rational care.’

TCM has been the subject of controversy within China. In 2006, the Chinese scholar Zhang Gongyao triggered a national debate when he published an article entitled ‘Farewell to Traditional Chinese Medicine,’ arguing that TCM was a pseudoscience that should be abolished in public healthcare and academia. The Chinese government however, interested in the opportunity of export revenues, has taken the stance that TCM is a science and has continued to encourage its development.

Since TCM has become more popular in the Western world, there are increasing concerns about the potential toxicity of many traditional Chinese herbal remedies including plants, animal parts and minerals. Some of these products may contain toxic ingredients or are contaminated with heavy metals, such as lead, arsenic, copper, mercury, thallium and cadmium – constituting serious health risks. Botanical misidentification of plants can cause toxic reactions in humans. These products are often imported into western countries illegally without government monitoring or testing, thus increasing the safety risks.

Many adverse reactions are due misuse or abuse of Chinese medicine. For instance, the misuse of the dietary supplement Ephedra (containing ephedrine) can lead to adverse events including gastrointestinal problems as well as sudden death from cardiomyopathy. Products adulterated with pharmaceuticals for weight loss or erectile dysfunction are some of the main concerns. TCM herbal remedies have been a major cause of acute liver failure in China.

Threats to endangered species

As mentioned earlier, TCM herbal remedies can include animal parts as well as plants. Some TCM textbooks still recommend preparations containing animal tissues, despite the lack of evidence of their efficacy. Parts of endangered species used as TCM herbal remedies include rhinoceros horns, tiger bones, Saiga antelope horns and dried seahorses.

Poachers supply the black market with these rare animal parts, with rhino horns literally being worth their weight in gold. The horns are made of keratin, the same type of protein that makes up hair and fingernails. They are ground into dust and used as TCM ingredients. In Europe and Vietnam, rhino horn is falsely believed by some to have aphrodisiac properties, but this belief is not part of TCM.

White Rhinoceros and calf caked in mud. Source: Wikimedia Commons

As a result of this demand, the world’s rhino population has reduced by more than 90 percent over the past 40 years. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List identifies one of the five modern rhino species as recently extinct and three as critically endangered. The West African Rhinoceros was declared totally extinct in November 2011. The northern sub-species of the White Rhinoceros is presumed extinct in the wild, with only a few individuals left in captivity. As of 2015, only 58-61 individuals of the Javan Rhinoceros remain in Ujung Kulon National Park, Java, Indonesia. The last Javan rhino in Vietnam was reportedly killed in 2011. There were 320 Sumatran rhinoceroses left in 1995, and these had dwindled to 216 by 2011.

In 1993, China signed the 171-nation Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) treaty and removed rhinoceros horn from the Chinese medicine pharmacopeia, administered by the Ministry of Health. In 2011, the Register of Chinese Herbal Medicine in the United Kingdom issued a formal statement condemning the use of rhinoceros horn. A growing number of TCM educators is also speaking out against the practice. Discussions with TCM practitioners to reduce the use of rhino horn, has met with mixed results, because some TCM practitioners still consider it a life-saving medicine of a better quality than its substitutes.

Tigers once ranged widely across Asia, from Turkey in the west to the eastern coast of Russia. Over the past 100 years, they have lost 93% of their historic range, and have been largely eliminated from large areas of Southeast and Eastern Asia.

South Chinese Tiger. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the 1940s, the Siberian tiger was on the brink of extinction with only about 40 animals remaining in the wild in Russia. As a result, anti-poaching controls were put in place by the Soviet Union and a network of protected zones were instituted, leading to a rise in the population to several hundred. Poaching again became a problem in the 1990s, when the economy of Russia collapsed. In 2005, there were thought to be about 360 tigers in Russia, though these exhibited little genetic diversity. However, in a decade later, the Siberian tiger census was estimated to be from 480 to 540 individuals.

The remaining six tiger subspecies have been classified as endangered by IUCN. The global population in the wild is estimated to number between 3,062 and 3,948 individuals, down from around 100,000 at the start of the 20th century, with most remaining populations occurring in small pockets isolated from each other, of which about 2,000 exist on the Indian subcontinent.

Major reasons for tiger population decline include habitat destruction, habitat fragmentation and poaching. Demand for tiger parts for use in TCM has also been cited as a major threat to tiger populations. Having earlier rejected the Western-led environmentalist movement, China changed its stance in the 1980s and became a party to the CITES treaty. By 1993 it had banned the trade in tiger parts, and this diminished the use of tiger bones in traditional Chinese medicine. Nevertheless, the illegal trading of tiger parts in Asia has become a major black market industry and governmental and conservation attempts to stop it have been ineffective to date

The Saiga antelope is a critically endangered species that originally inhabited a vast area of the Eurasian steppe zone from the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains and Caucasus into Dzungaria and Mongolia. They also lived in Beringian North America during the Pleistocene. Today, the dominant subspecies is only found in one location in Russia and three areas in Kazakhstan. Fewer than 30,000 Saiga antelopes remain. Organized gangs illegally export the horn of the antelopes to China for use in TCM herbal remedies.

Saiga antelope: skull and taxidermy. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Demand for the horns has wiped out the population in China, where the Saiga antelope is a Class I protected species, and drives poaching and smuggling. Under the auspices of the Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), also known as the Bonn Convention, the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) Concerning Conservation, Restoration and Sustainable Use of the Saiga Antelope was concluded and came into effect 24 September 2006. The Saiga’s decline being one of the fastest population collapses of large mammals recently observed, the MoU aims to reduce current exploitation levels and restore the population status of these nomads of the Central Asian steppes.

Seahorse is the name given to 54 species of small marine fishes in the genus Hippocampus. ‘Hippocampus’ comes from the Ancient Greek word hippos meaning ‘horse’ and kampos meaning ‘sea monster’.

Drying seahorses for TCM. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Because data is lacking on the sizes of the various seahorse populations, as well as other issues including how many seahorses are dying each year, how many are being born, and the number used for souvenirs, there is insufficient information to assess their risk of extinction, and the risk of losing more seahorses remains a concern. Some species, such as the Paradoxical Seahorse may already be extinct. Coral reefs and seagrass beds are deteriorating, reducing viable habitats for seahorses.

Seahorse populations are thought to be endangered as a result of overfishing and habitat destruction. Despite a lack of scientific studies or clinical trials, the consumption of seahorses is widespread in traditional Chinese medicine, primarily in connection with impotence, wheezing, nocturnal enuresis, and pain, as well as labor induction. Up to 20 million seahorses may be caught each year to be sold for such uses.

Import and export of seahorses has been controlled under CITES since 15 May 2004. However, Indonesia, Japan, Norway, and South Korea have chosen to opt out of the trade rules set by CITES. The problem may be exacerbated by the growth of pills and capsules as the preferred method of ingesting seahorses. Pills are cheaper and more available than traditional, individually tailored prescriptions of whole seahorses, but the contents are harder to track. Seahorses once had to be of a certain size and quality before they were accepted by TCM practitioners and consumers. Declining availability of the preferred large, pale, and smooth seahorses has been offset by the shift towards prepackaged preparations, which makes it possible for TCM merchants to sell previously unused, or otherwise undesirable juvenile, spiny, and dark-coloured animals. Today, almost a third of the seahorses sold in China are packaged, adding to the pressure on the species.

Dried seahorse retails from US$600 to $3000 per kilogram, with larger, paler, and smoother animals commanding the highest prices. In terms of value based on weight, seahorses retail for more than the price of silver and almost that of gold in Asia.

The traditional practice of using endangered species is becoming controversial within TCM. Modern TCM texts discuss substances derived from endangered species in an appendix, emphasizing alternatives.

Like other varieties of quackery, TCM offends our sense of rationality by being a useless waste of time and money. But it is also harmful to humans and other species, in terms of diversion from effective therapies, risks of toxicity and threats to the survival of endangered species.

Tim Harding B.Sc. B.A. is a former Director of Flora and Fauna, in charge of protecting endangered species in Victoria.

References

Stephen Barrett. “Be Wary of Acupuncture, Qigong, and ‘Chinese Medicine’

Ian Musgrave et al What’s in your herbal medicines? The Conversation, 13 December 2015.

Traditional Chinese Medicine, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, Traditional Chinese Medicine: An Introduction

(more to be added)

Copyright notice: © All rights reserved. Except for personal use or as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act, no part of this website may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, communicated or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All inquiries should be made to the copyright owner, Tim Harding at tim.harding@yandoo.com, or as attributed on individual blog posts.

If you find the information on this blog useful, you might like to consider supporting us.