‘Rather than being a ‘perversion’ of Islam, it is truer to say that the version of Islam espoused by ISIS, while undoubtedly the worst possible interpretation of Islam, and for Muslims and non-Muslims everywhere obviously the most destructive version of Islam, is nevertheless a plausible interpretation of Islam.’

Tag Archives: Islam

HuffPo ignores Islam in report on three British terror attacks

Here’s today’s Puffho piece on the terror attacks in London last night (click screenshot to go to article).

We do not yet know for certain whether the latest attacks these were committed by Islamists, but it seems likely, and the New York Times reported this:

Britain’s home secretary, Amber Rudd, said on Sunday that the government was confident the attackers were “radical Islamist terrorists.” Speaking on ITV television, Ms. Rudd said, “As the prime minister said, we are confident about the fact that they were radical Islamist terrorists, the way they were inspired, and we need to find out more about where this radicalization came from.”

https://twitter.com/Imamofpeace/status/871154639885844481

PuffHo also mention the Westminster Bridge attack and the Ariana Grande concert bombing, clearly instances of Islamist terrorism. There is not a single mention of “ISIS”, “Islam”, or “Muslim” in the whole article. That, of course, is deliberate, as the HuffPo wants…

View original post 137 more words

Filed under Reblogs

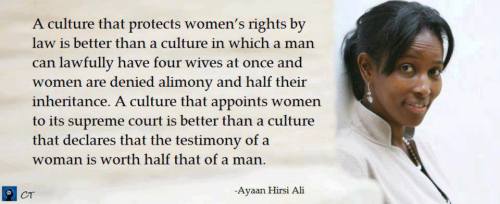

Ayaan Hirsi-Ali – A question and answer session with one of the world’s most high profile critics of Islam

From the Australian Rationalist (Melbourne), v.104, Autumn 2017: 16 – 19. Journal of the Rationalist Society of Australia, www.rationalist.com.au

The Somali-born feminist Ayaan Hirsi is one of the world’s most prominent critics of Islam and how Islamic societies treat women. In particular, she has targeted the barbaric practice of female genital mutilation, which she was subjected to.

Hirsi has had an exceptionally high profile career in politics and in other areas of public life. In 2003, she was elected to the Netherlands’ lower house of parliament as a representative of the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), but a controversy relating to the validity of her Dutch citizenship led to her subsequent resignation.

In 2004, she collaborated on a controversial short movie with Theo van Gogh called Submission, which depicted the oppression of women under Islam. This resulted in death threats against the two creators, and the eventual assassination of Van Gogh later that year.

In 2005 she was named by Time magazine in the 100 most influential people in the world. She has received several awards, including the Moral Courage Award. She subsequently emigrated to the United States where she founded the women’s rights organisation the AHA Foundation. She is married to Scottish historian and public commentator Niall Ferguson, and has one child.

Hirsi has published five books, including two autobiographies. Her latest book Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now, published in 2015, argues that a religious reformation is the only way to end Islamic terrorism, sectarian warfare, and the persistent repression of women and minorities.

Hirsi’s tone is often vigorous, even combative. In her latest book, for example, she declares that her intention is: “To make many people — not only Muslims but also Western apologists for Islam — uncomfortable.”

It is therefore unsurprising that she has attracted considerable criticism. This ranges from the extreme to the more reasoned. The extreme end was in evidence with the outrageous comments by Linda Sarsour, a Palestinian-American activist and executive director of the Arab American Association of New York, who was a principal organiser of the women’s march on Washington after the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency. Sarsour said of Hirsi that she did not “deserve” to be called a woman.

More moderate criticisms tend to focus on Hirsi’s generalisations about Islam. For example, Max Rodenbeck commented in the New York Review of Books:

“Hirsi Ali is probably quite correct to assert that, while it is particularly noisy and violent, the jihadist ‘ Medina ’ end of the Islamic spectrum is narrow and thinly populated compared to the much larger ‘ Mecca ’ group. She is also right that the outspokenly critical Muslims are even less numerous. But surely the 1.5 billion ‘ Mecca ’ Muslims do not all fit into a single hapless category. Like the members of any great religion, one might imagine they instead have a diversity of views, as designations that Muslims use for one another, such as, for example, Salafist, Sufi, Ismaili, Zaidi, Wahhabist, Gulenist, Jaafari, and Ibadi, would suggest.” (New York Review of Books, 3 December 2015).

Rodenbeck also questioned some of Hirsi’s other claims. Sharia law, he said, is not a homogenous, rigid set of laws. Instead, he claimed, it “is an immense amalgam of texts and interpretations that has evolved along parallel paths within five major and numerous minor schools of law, all of them equally valid to their followers.”

Hirsi’s counter, however, is that while there are variations of sharia law, the underlying assumptions about the status of women and their rights is common across all variants.

The practice of martyrdom and suicide bombing, Rodenbeck says, is also comparatively recent, dating from the 1980s. “The four main schools of Sunni jurisprudence, including arch-conservative Saudi clerics, all concur that suicide is a serious sin,” he notes.

Likewise, there are those who question the claim that Islam has aggressively imposed itself on infidels. The history of the Ottomans, for example, suggests the opposite; that non-Muslims in the conquered countries were allowed to practice their religion freely. Hirsi responds by pointing to current behaviour in Islamic countries.

If there are points of disagreement about what Islam is, what is not in doubt is Hirsi’s courage. She went to the Netherlands to escape an arranged marriage in Kenya and was granted refugee status and, ultimately, given a Dutch passport.

She earned a Master’s degree that led her into outreach work with Muslim immigrant women, initially in affiliation with the Labour party. Witnessing the repression of women in immigrant communities, and deeply shocked by the 11 September 2001 attacks, she became a vocal defender of universal women’s rights, which she believes are ignored in Islamic societies.

In making her case against the treatment of women in Islamic societies, something that has sparked the ire of the liberal left, especially in America , Hirsi has exposed the selectivity common in Western feminism. As she has pointed out, there have been large demonstrations against the decision by President Trump to deny entry to people from some countries that have a majority Muslim population.

Where, she asked in a television interview, was the outrage when, in 2015, a woman in Pakistan was condemned to death for allegedly blaspheming? Or the many other barbaric acts against women in Islamic countries?

Thus when Hirsi describes the leaders of these protestors as “fake feminists” who do not genuinely speak on behalf of Islamic women, she is making a case for the universality of human rights: the belief that what is considered unacceptable in one country should be considered unacceptable in all countries. That sits uncomfortably with many left-wing activists, who have had difficulty resolving the tension between arguing for universal rights on the one hand, and being tolerant of cultural differences on the other.

Australian Rationalist interviewed Ayaan Hirsi, who is being brought to Australia by Think Inc. (See dates below.)

Australian Rationalist (AR): You have been subjected to an enormous amount of pressure, ranging from death threats to, more recently, the insults from Linda Sarsour. Psychologically how do you deal with that sort of thing?

Ayaan Hirsi: There is no psychology to it. I have been doing this since 9/11 of 2001. I listen to women like Linda Sarsour and think: “She doesn’t know me and 1 don’t know her.” I know that she is devoted to Islamic law and the implementation of Islamic law, and so I think of her as a fake feminist. And I think other people should do their due diligence when they march with people like her.

She is in fact a proponent of Islamic law and there is no principle that is more demeaning and degrading and dehumanising to women than Islamic law. I fight for what I believe in, which is universal human rights and the equality between men and women before the law. And religious tolerance and rights for gay people and the LGBT community. They should have every right that heterosexuals have. That is what I believe in and that is what I fight for.

I understand that she and I are ideological opponents. I do not stoop to the kind of language that Sarsour uses, but it is very clear to me that she hates me because of my ideas.

AR: There seems to be a lot of hatred and the debate seems to be becoming more extreme. Where do things stand? How likely there is to be constructive ways of moving forward?

Hirsi: The trouble is that with the values that are in Islamic law a compromise is just not possible. You are not going to offer a little bit of equality between men and women. [Those on the other side] are not going to say that we will go the other way and kill apostates or strip them of their rights. There is no middle ground there. It is characteristic of Islamic extremism that they just don’t argue their position.

I have spent hours and hours thinking about how I should sell the ideas. What is wrong with my way of looking at the world? I can be persuaded up to a certain point, but there are some values I will never give up. I will never use violence. Whereas Islamic extremists disagree with that and use the harshest language possible, and they are very happy also to use violence.

A lot of people say Islam is the fastest growing religion in the world. Well, you know, there are so many Muslims who are terrified of coming out and saying that they are not Muslims any more. They are afraid of their own families.

AR: If there is no room for compromise, how can you reform Islam? Is there a way of doing it?

Hirsi: There is, because I am one of those people who believe that ideas — I believe Islam is a human idea — can be changed in the minds of people. I am now seeing, with relief, more and more Muslims coming out and saying this moral code that is Islamic law is false. They can’t align it with their conscience.

The question and discussion I have with some of these Muslim reformers is to ask the question: “What is it about Islam that should be shed? What should be seen in an historical context and belongs in a museum and not in real life?” I identify five principles [that need to be rethought]. Following blindly the edicts in the Koran and Mohammed’s conduct. Believing that life after death is more important than life before death. Believing that some individuals occupy the commanding heights, have the power to enforce the law. And the practices of sharia law and jihad.

These are the key components that Muslim reformers should gather around and try to persuade Muslims to change their minds around that. It is going to be a very long struggle.

AR: I have heard it argued that some people say some of this is not true to Mohammed. How many of those principles are genuinely stated by Mohammed rather than added later?

Hirsi: There are two discussions that come up every time that Islamic extremism is discussed. One is a set of Muslims saying: “Look, Mohamed never said these things and he never did it and it is not in the Koran, and the scripture and history of Islam is one of peace.”

That is easily debunked; you just look at the Koran and you look at Mohammed, and I am not talking about what non-Muslims say about Mohammed, I am talking about the hagiographic biography of Mohammed written by people who believe in him.

When we look at occasions when Islamic law is implemented, what do you see? Do they look very peaceful to you? These are places that have internal repression. A good example is Iran . Another good example is Saudi Arabia . So that claim is easily debunked.

The other issue that arises here — if we fantasise about an ideal world where people, Muslims, will stop denying what Islam actually says — is it possible for them to be Muslim and at the same time criticise the Prophet Mohammed?

Ultimately, Muslims will have to find their own solutions to that. It is possible, in my view, for Muslims to shed all the violence and intolerant principles and remain Muslims. Because they will then adhere to the example of the Prophet Mohammed in Mecca when he prayed, and he fasted, and he was religious in the way we think of religion today. It is only after he goes to Medina that he starts to develop not just a religious doctrine but a political and military doctrine.

AR: Another argument is that many of the problems in the Middle East are more cultural rather than religious. In some of the societies that do Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), Christians do it as well as the Muslims. So it is attributed more to a cultural history rather than a religion. What is your view of that kind of position?

Hirsi: The practice of cutting and sewing the genitals of girls and women predates Islam. It was there before Islam, and it happens in places where people are not Muslim at all. What makes it fit into Islam is that there is this hadith — hadith is a narrative. People saying that the Prophet Mohammed had recommended it. The view of modesty, virginity, the position of the woman and her honour in Islam is what makes it prevalent in Muslim countries.

You could argue, technically, that even if Mohammed did recommend it, a recommendation is different from an obligation: you don’t have to do it. But even if that is the case, it is really about the position of women in Islam. It is part and parcel of measures such as having women covered from head to toe. Or having women be wards for the rest of their lives. Forcing children into marriage. They are never seen as adults.

This is an attitude towards women, and if you see it in that context you will understand why the Muslim Brotherhood introduced the practice into Indonesia where before that it was never practised.

There are several places in the world where Islam has transported the practice of female genital mutilation in the name it Islam. So who can deny that it is Islamic? We don’t want to have empty discussions. We want to really talk about the core problem, and the core of the problem is the attitude to women. Simply refusing to recognise women as fellow human beings.

AR: Is there actually a theological position in Islam that men and women aren’t equal.

Hirsi: It is implicit and explicit. The Koran, the hadith and the practice of Islam makes women subordinate to men. Women are not seen as autonomous owners of their own bodies. You could argue that that is Arab culture and many other non-Muslim societies. But you cannot argue that men and women are regarded as equal in Islam.

AR: Is that said overtly in a theological way in Islam?

Hirsi: Yes, it is. There are many ways it is said theologically. For instance, the wife has to obey without question. If she disobeys, or if he fears her disobedience, he warns her and he can leave her alone in bed or beat her if he needs to. This is at the core of Islam’s attitude to women. Even in cases where Islam is not implemented in the sense of hands and feet cut off, or people are beheaded, it is still the case in those places that the family law, which is the law of the land, strips women of their rights.

I am talking here about more progressive countries in North Africa . Even where they have the laws on the books that are very European, still the way that people live is to subordinate women to men. All of this is argued in the name of Islam — all of it.

AR: What is your view of Donald Trump at the moment? Are you a supporter of what he is doing, are you indifferent, or are you against what he is doing. Particularly the refugee ban, but also his general positions?

Hirsi: He gave a speech in August last year, which I thought was very heartening. When he said we have to call Islamic extremes [sic: extremism?] by its name. He put it in the same realm as the totalitarian ideologies of the twentieth century: Nazism, fascism and communism. He said the threat of the day is Islamic extremism. He said if he was elected president that was how he was going to fight it. He was going to see it as an ideology.

He has only been in office in 13 or 14 days; he has been very busy. but I think his basic premise is right. Now we just need to develop a very effective tool box to fight it as an ideology.

The trouble with Obama’s presidency and even George W. Bush’s presidency was that they focused only on the violence and therefore limited the tool box of measures that they could apply. They confined themselves only to surveillance and military tactics.

But you can’t really bomb bad ideas out of people’s heads. Islamic law is a bad idea and if we develop a counter-narrative, a counter-set of ideas, then sell that, then I think we will be able to persuade lots of Muslims to abandon Islamic law.

AR: What arc the elements of that narrative. What does it look like?

Hirsi: One of the tools that Islamic extremists use to recruit people and inspire them is to say that there are all these rewards promised in the after-life. We could develop a counter-narrative of life where they say we love death more than life; we could say we love life more than death. Here is a narrative of life.

But that means you are going to talk about life after death, and you will be accused of blasphemy and attacking Islam and all the rest of it. You could also point to open liberal societies, and even though they are not perfect societies, they are prosperous. People grow old and die in their beds most of the time. That the idea of liberty and liberalism is superior to the idea of Islamic law.

You can point it out to those they target: that is, the young and impressionable men, and say: “Why are you fleeing your country of origin. Why are you trying to get to the United States of America ? Because America implements the idea of liberty, and what you are promised as a young man or a young woman when it comes to sharia law is a cruel society, cruel economics. It is inhumane.”

So you have a counter-narrative in exactly the same way as we had in the Cold War. We used all sorts of cultural norms and cultural persuasive tools to get to the people behind the Iron Curtain and persuade them that Marxism was a nihilist, violent and empty ideology. It looked good on paper, but it was not when put into practice.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali will be appearing at the Brisbane Convention & Exhibition Centre on 6 April, the Festival Hall in Melbourne on 7 April, Darling Harbour Theatre in Sydney on 8 April, and in the Llewellyn Hall in Canberra on 10 April. All starting times are 7 p.m. https://www.thinkinc.org.au/events/hirsi-ali/

Ayaan Hirsi Ali on cultural inequality

Ayaan Hirsi Ali (born 1969) is a Somali-born Dutch-American activist, author, and former Dutch politician. She is has been a vocal critic of Islam, as well as a feminist and atheist. Ayaan Hirsi Ali is currently a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford, and the founder of the AHA Foundation, which exists to protect women and girls from abuses. She will visit Australia in early April to discuss reforming Islam.

Filed under Quotations

Joe Hildebrand on free speech

“This should make the blood run cold in any free-thinking, independent, intelligent person.” – Joe Hildebrand on Australia’s Grand Mufti’s calls to make it illegal to criticise Muslims about their religion.

Australians should also worry about white extremists in our own backyard

Mark Briskey, Curtin University

The proliferation of terrorist attacks in the US, Europe, the Middle East, Asia and Africa saturate the media with attention to and analysis of these outrages. From the murder of a Catholic priest in France to the massacre of 80 Hazara people in Kabul, these lead us inexorably to question the origins of such attacks and why these extremists claim Islam as a justification.

Equally, the focus upon the Man Haron Monis inquest as well as emerging details of the Anzac day plot capture our attention in Australia. Without alternative commentary, this leads many of us to equate Islam with terrorism, false as this may be.

But some headlines are now informing us of a “new” risk, with the arrest on terrorism charges of a white “nationalist extremist” from an avowedly right-wing organisation.

A history of foreign fighters and extremist violence

Is this something new? Of course it is not. Despite the recent focus on those who malign the name of Islam in the name of terrorism, Australia has a long history of terrorism.

This is true, too, of our history of foreign fighters. They have been every bit as diverse as the multicultural country we live in. Though we argue the relative merits and ethics of particular causes, Australians have travelled to foreign conflicts since before federation.

Australians have been involved in conflicts from the American Civil War and fighting fascism in the Spanish Civil War to more recent examples of individuals fighting for Islamic State and against it. Some have involved themselves in continuing conflicts and causes far from their adopted country of Australia. One example is the Ustaša and their activities against the former Yugoslavia.

While many may applaud involvement in some of these conflicts, a dark side of this has been the continuing presence of far-right-wing neo-Nazi groups in Australia. There has been analysis of why the more mainstream of these groups have achieved recent electoral success – a recent John Safran documentary is particularly good at teasing this out. However, the underside of the far right is more pernicious and potentially more dangerous.

Neo-Nazi members have been guilty of ongoing violence against migrant communities. The bashing of Minh Duong was a particularly significant example of these groups’ commitment to violence.

Don’t neglect radicalisation on the right

Australia has suffered right-wing extremist violence in the past, though none comparable to the Breivik massacre in Norway or the McVeigh bombing in the US. However, the arrest on the weekend should alert us that it is imperative that any consideration of counter-radicalisation should include members of the extreme right.

The arrest follows a disturbing series of vile attacks against the Muslim community around Australia. These range from those random rants of racists abusing Muslims or suspected Muslims on public transport to attacks in which mosques have been set alight and daubed with racist graffiti, coming on occasion very close to causing injury or death.

Those who subscribe to an extremist Islamic narrative may indeed give us cause to fear their actions and the influence of technology-assisted radicalism. Equally, we should fear members of the far right who have access to a poisonous blend of neo-Nazi motivation that is as global and as accessible as their chosen information technology device.

As we urge representatives of the Muslim community to look for solutions to the apparent siren-like attraction of violent extremism for those in disenfranchised communities, so we must also robustly reject the simplistic and unauthentic rhetoric that right-wing parties peddle about Islam.

A good place to begin would be to have those government members who make a noise about the threat of Islamist extremism, such as George Christensen and Cory Bernardi, as well as One Nation’s Pauline Hanson, to set the example and reject right-wing extremism in all its forms.

![]() Mark Briskey, Senior Lecturer, National Security and International Relations, Curtin University

Mark Briskey, Senior Lecturer, National Security and International Relations, Curtin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. (Reblogged by permission). Read the original article.

Filed under Reblogs

Maajid Nawaz and the New York Times weigh in on the Nice attacks

Yes, I’ve had to add a new category of post: “terrorism.” It’s sad. When I wrote about the Nice attack yesterday, I suspected that the perpetrator, Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, might have religious motivations, or at least be working for an organization like ISIS, but there was little information. This morning I learned from CNN that ISIS has now claimed credit for the murders:

In an online statement by the terror group’s media agency Amaq and circulated by its supporters, it said the person behind the attack is an ISIS “soldier.”

Five others, including Bouhel’s wife, have been arrested: the CNN piece gives more detail. It’s not clear whether Bouhel was actually sent by ISIS to do the deed, or was a sympathizer working under their direction. Or, I suppose, ISIS could be lying, but I’m not aware that they’ve falsely taken credit for an attack.

Yesterday Maajid Nawaz weighted in…

View original post 1,794 more words

Filed under Reblogs

Nick Cohen on reforming Islam: don’t look to faith to fix itself

Cohen’s new piece in the Guardian, “Don’t look to the Pope for enlightenment values“, is his usual good stuff, criticizing the Vatican for calling Charlie Hebdo anniversary cover “blasphemous,” and especially for the hypocrisy of a Church whose history showed and whose scripture still shows approbation for awful crimes. But there’s one bit of the piece that struck me strongly.

First, though, we have Cohen’s definition of the Enlightenment, taken from Kant. It’s as good as any I’ve seen:

Kant provided a guide for the uninitiated. What is Enlightenment? he asked in 1784…

View original post 866 more words

Filed under Reblogs

Jeff Tayler on the vilification of Muslim and ex-Muslim progressives

Jeff Tayler seems to have moved his “blog” articles on religion and politics from Salon to Quillette. I approve. In late April, Jeff wrote a widely-read piece on Quillette whose title tells it all: “In defense of Sam Harris.” Now he’s written a new piece that might well be called “In defense of Maajid Nawaz,” except that it’s a defense of all progressive Muslims and ex-Muslims, so its real title is “Free speech and Islam—the Left betrays the most vulnerable.”

It might also have been called “The perfidy of Nathan Lean,” that unctuous defender of all things Islam and ample employer of the term “Islamophobia.” For it was Lean who wrote a New Republic piece on Maajid Nawaz that was one of the most odious and unscrupulous pieces of “journalism” I’ve ever seen. (It may not be irrelevant that Lean is employed at the Saudi Arabian-funded Prince…

View original post 704 more words

Filed under Reblogs

The Dark Ages

by Tim Harding

(An edited version of this essay was published in The Skeptic magazine,

March 2016, Vol 35, No. 1, under the title ‘In the Dark’).

Like other skeptics, I often despair at the apparent decline in the public understanding of science. Anti-science, pseudoscience, quackery, conspiracy theories and the general distrust of experts seem to be on the rise. I sometimes even wonder whether we in danger of regressing into a new dark age.

So what do we mean by a ‘dark age’? Was there really a dark age in post-Roman Europe? If so, what were its most likely causes? These questions are difficult to answer, and not just because of disagreements among historians. The difficulty is in some ways circular – we call the post-Roman period a ‘dark age’ because we don’t know enough about it (relative to the periods before and after); and we don’t know enough about it because not much was written down at the time.

My own observation is that western civilisation has already suffered two dark ages about 1300 years apart. (There was an earlier dark age in Ancient Greece from around 1100 to 800 BCE). If this ‘trend’ is repeated we should be due for another one in a couple of hundred years’ time.

My own observation is that western civilisation has already suffered two dark ages about 1300 years apart. (There was an earlier dark age in Ancient Greece from around 1100 to 800 BCE). If this ‘trend’ is repeated we should be due for another one in a couple of hundred years’ time.

The term ‘Dark Ages’ commonly refers to the Early Middle Ages, which was the period of European history lasting from the 5th century to approximately 1000 CE. The Early Middle Ages followed the decline of the Western Roman Empire and preceded the Central Middle Ages (c. 1001–1300 CE) and the Late Middle Ages (1300-1500CE). The period saw a continuation of downward trends begun during late classical antiquity, including population decline, especially in urban centres, a decline of trade, and increased translocation of peoples. There is a relative paucity of scientific, literary, artistic and cultural output from this time, especially in Western Europe.

Historians suggest that there were several causes of this decline, including the rise of Christianity. The other causes are often overlooked, especially by antitheists trying to score points such as ‘look what happened when your mob was in charge!’. So like good skeptics, let’s examine the historical evidence.

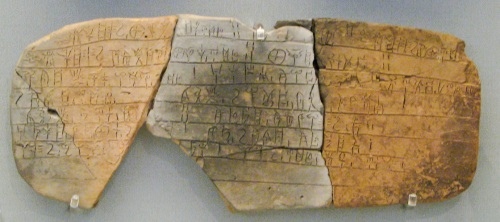

The Greek Dark Age

The first European dark age occurred in ancient Greece from around 1100 to 800 BCE. The archaeological evidence shows a collapse of the Mycenaean Greek civilization at the outset of this period, as their great palaces and cities were destroyed or abandoned and vital trade links were lost. Unfortunately, their Linear B script also disappeared, leaving us with no written accounts of what really happened or why.

Linear B script. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Legend has it that Greece was invaded by the mysterious Dorians from the north and/or the Sea Peoples of uncertain origin but possibly from the Black Sea area. The archeological evidence is of little help to us other than showing a simpler geometrical style of pottery art than that of the Mycenaeans, hinting at occupation by a different culture.

Geometric (9th-7th century BCE) pottery from Melos in Greece. Source: Wikimedia Commons

There is archeological evidence of a revival of Greek trade at the beginning of the 8th century BCE, coupled with the appearance of a new Greek alphabet system adapted from the Phoenicians which is still in use today. This led to creation of western civilisation’s oldest extant literary works, such as Homer’s The Odyssey and The Iliad. From succeeding centuries we have been bequeathed major texts of ancient Greek drama, history, philosophy and science.

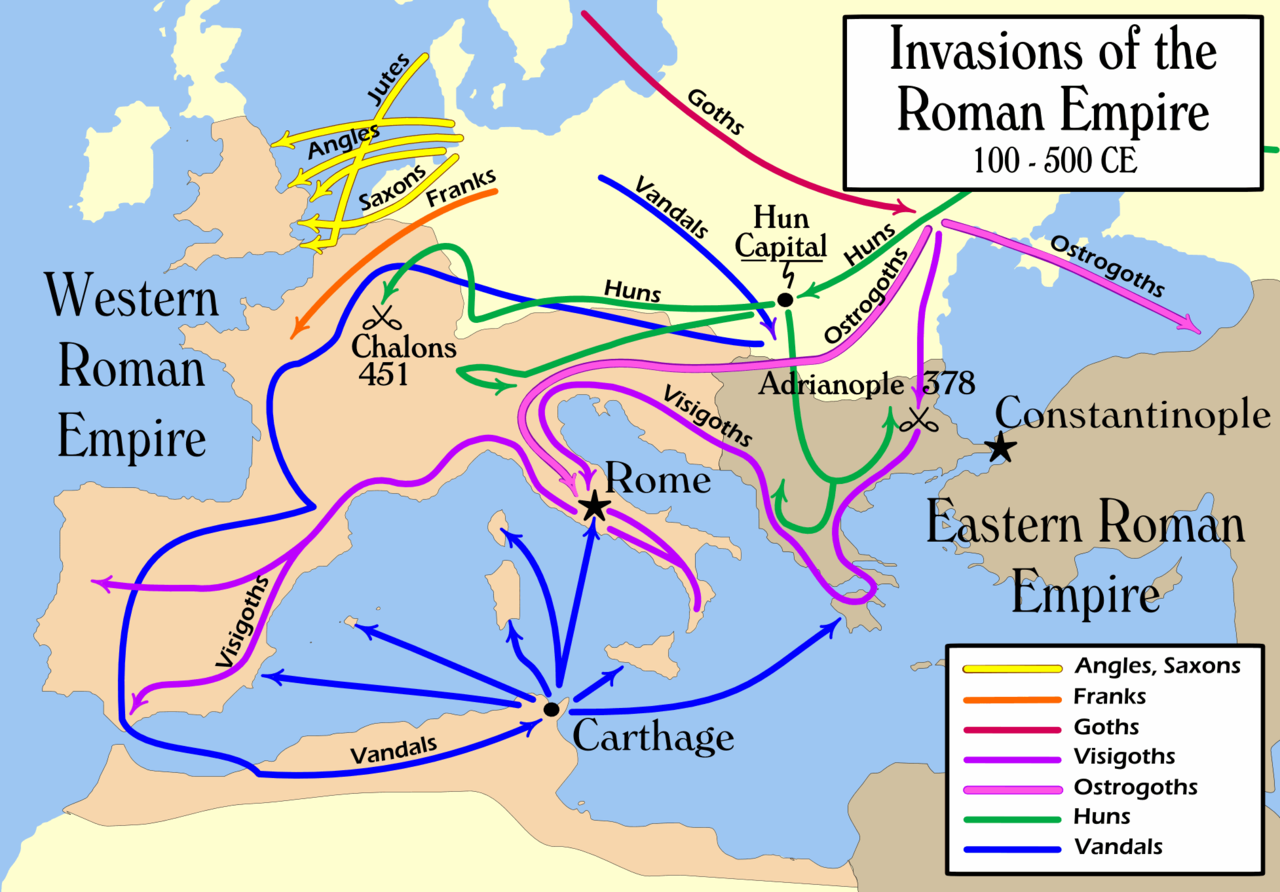

The decline of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire reached its greatest territorial extent during the 2nd century CE, reaching from Babylonia in the East to Spain in the West, Britain and the Netherlands in the North, to Egypt and North Africa in the South. The following two centuries witnessed the slow decline of Roman control over its outlying territories. The Emperor Diocletian split the empire into separately administered eastern and western halves in 286CE. In 330CE, after a period of civil war, Constantine the Great refounded the city of Byzantium as the newly renamed eastern capital, Constantinople.

During the period from 150 to 400CE, the population of the Roman Empire is estimated to have fallen from 65 million to 50 million, a decline of more than 20 percent. Some have connected this to the Dark Ages Cold Period (300–700CE), when there was a decrease in global temperatures which impaired agricultural yields.

In 400CE, the Visigoths invaded the Western Roman Empire and, although briefly forced back from Italy, in 410CE they sacked the city of Rome. The Vandals again sacked Rome in 455CE. The deposition of the last emperor of the west, Romulus Augustus, in 476CE has traditionally marked the end of the Western Roman Empire. The Eastern Roman Empire, often referred to as the Byzantine Empire after the fall of its western counterpart, had little ability to assert control over the lost western territories. Although the movements of peoples during this period are usually described as ‘invasions’, they were not just military expeditions but migrations of entire peoples into the empire. These were mainly rural Germanic peoples who knew little of cities, writing or money. Administrative, educational and military infrastructure quickly vanished, leading to the collapse of the schools and to a rise of illiteracy even among the leadership.

For the formerly Roman area, there was another 20 percent decline in population between 400 and 600CE, or a one-third decline between 150-600CE which had significant economic consequences. To make matters worse, the Plague of Justinian (541–542CE), which has since been found to have been bubonic plague, recurred periodically for 150 years – killing as many as 50 million people in Europe. The population of the city of Rome itself declined from about 450,000 in 100CE to only 20,000 during the Early Middle Ages. The city of London was largely abandoned.

In the 8th century, the volume of trade reached its lowest level, indicated by very small number of shipwrecks found in the western Mediterranean sea.

One of the main consequences of the fall of Rome was breakdown of the strict Roman law and order, resulting amongst other things in the running away of slaves who had performed most of the labour. Less food and fibre was produced on farms, resulting in people leaving the cities to less efficiently grow their own. Lower agricultural activity resulted in reforestation, or in other words the forests naturally grew back. Travel and trade by land became less safe, exacerbating the economic decline.

The role of the Christians

The Catholic Church was the only centralized institution to survive the fall of the Western Roman Empire intact. It was the sole unifying cultural influence in Western Europe, preserving Latin learning, maintaining the art of writing, and preserving a centralized administration through its network of bishops ordained in succession. The Early Middle Ages are characterized by the control of urban areas by bishops and wider territorial control exercised by dukes and counts. The later rise of urban communes marked the beginning of the Central Middle Ages.

During the Early Middle Ages, the divide between eastern and western Christianity widened, paving the way for the East-West Schism in the 11th century. In the West, the power of the Bishop of Rome expanded. In 607CE, Boniface III became the first Bishop of Rome to use the title Pope. Pope Gregory the Great used his office as a temporal power, expanded Rome’s missionary efforts to the British Isles, and laid the foundations for the expansion of monastic orders.

The institutional structure of Christianity in the west during this period is different from what it would become later in the Central Middle Ages. As opposed to the later church, the church of the Early Middle Ages consisted primarily of the monasteries. In addition, the papacy was relatively weak, and its power was mostly confined to central Italy. Religious orders wouldn’t proliferate until the Central Middle Ages. For the typical Christian at this time, religious participation was largely confined to occasionally receiving mass from wandering monks. Few would be lucky enough to receive this as often as once a month. By the end of the Dark Ages, individual practice of religion was becoming more common, as monasteries started to transform into something approximating modern churches, where some monks might even give occasional sermons. Thus the evidence for powerful centralised Christian control during the Dark Ages is lacking.

The Western European Dark Age

The concept of a Western European Dark Age originated with the Italian scholar Petrarch in the 1330s CE. Petrarch regarded the post-Roman centuries as ‘dark’ compared to the light of classical antiquity. The Protestant reformers of the 16th century had an interest in disparaging the ‘Dark Ages’ as an era of Catholic control, when they (the Protestants) thought that Christianity had ‘gone off the rails’. Later historians expanded the term to refer to the transitional period between Roman times and the Central Middle Ages (c. 11th–13th century), although in the 20th century the Dark Ages were contracted back to the Early Middle Ages (500-1000CE) again. I shall refer to this period in western Europe as ‘the Dark Ages’ from here on.

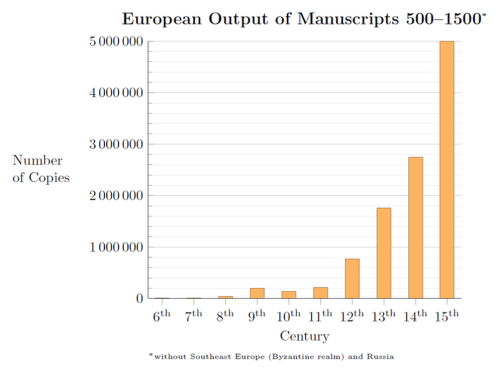

Evidence for the Dark Ages include the lack of output of manuscripts (both originals and copies), a lack of contemporary written history, general population decline, a paucity of inventions, a lack of sea trade, restricted building activity and limited material cultural achievements in general.

The lack of manuscripts in the Dark Ages compared to later Middle Ages is illustrated by the following graph.

The Romans were remarkable innovators. Their inventions of materials included kiln-fired bricks, cement, concrete, wood veneer, cast iron, glassware and surgical instruments. In construction, they invented paved roads, bridges, tunnels, aqueducts, arches, domes, dams, water supply, drainage, sewerage and even underfloor heating. Their production technology included the wheeled plow, the two-field crop system, harvesting machines, paddlewheel mills, the screw press, the force pump, steam power, gearing, pulleys and cranes. The Romans were also admired for their mining technology.

In contrast, hardly any new technology was invented during the Dark Ages. Nor were there any scientific discoveries of note; although science and mathematics continued to flourish in the Islamic world, as discussed below. Yet later in the Central Middle Ages, technological inventions included windmills, mechanical clocks, transparent glass, distillation, the heavy plow, horseshoes, harnesses, stirrups and more powerful crossbows. Architectural innovations enabled the building of larger cathedrals and faster ships.

The invention of the three-field system towards the end of the Dark Ages, coupled with higher temperatures and the heavy plow enabled higher agricultural yields, which kick-started economic recovery and the resumption of trade. Amongst other things, the three-field system created a surplus of oats that could be used to feed more horses. It also required a re-organisation of land tenure that led to manoralism and feudalism.

In the ancient world, Greek was the primary language of science. Advanced scientific research and teaching was mainly carried on in the Hellenistic side of the Roman empire, and in Greek. Late Roman attempts to translate Greek writings into Latin had limited success. As the knowledge of Greek declined, the Latin West found itself cut off from some of its Greek philosophical and scientific roots.

In the late 8th century, there was renewed interest in Classical Antiquity as part of the short-lived Carolingian Renaissance of the early 9th century CE. Charlemagne carried out a reform in education. From 787CE on, decrees began to circulate recommending the restoration of old schools and the founding of new ones across the empire. Institutionally, these new schools were either under the responsibility of a monastery (monastic schools), a cathedral, or a noble court. The teaching of dialectic (a discipline that corresponds to today’s informal logic) was responsible for the increase in the interest in speculative inquiry; from this interest would follow the rise of the Scholastic tradition of Christian philosophy. In the 12th and 13th centuries, many of those schools that were founded under the auspices of Charlemagne, especially cathedral schools, would become universities.

The expansion of Islam

After the death of the prophet Mohammed in 632CE, Islamic forces conquered much of the former Eastern Roman Empire and Persia, starting with the Middle East and Arabian Peninsula in the early 7th century, North Africa in the later 7th century, and much of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) in 711CE. This Islamic Empire was known as the Umayyad Caliphate. Its capital was the Spanish city of Cordoba, which by the 10th century CE had become the world’s largest city, with an estimated population of around 500,000.

The Umayyad Caliphate in 750 CE

The Islamic conquests reached their peak in the mid-8th century. The defeat of Muslim forces at the Battle of Poitiers in 732 led to the re-conquest of southern France by the Franks, but the main reason for the halt of Islamic growth in Europe was the overthrow of the Umayyad dynasty and its replacement by the Abbasid dynasty based in Babylon.

The works of Euclid and Archimedes, lost in the West, were translated from Arabic to Latin in Spain. The modern Hindu-Arabic numerals, including a notation for zero, were developed by Hindu mathematicians in the 5th and 6th centuries. Muslim mathematicians learned of it in the 7th century and added a notation for decimal fractions in the 9th and 10th centuries. In the course of the 11th century, Islam’s scientific knowledge began to reach Western Europe, via Islamic Spain.

Conclusions

The former Roman Empire was replaced by three civilisations – Western Europe, the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic Caliphate. The Dark Ages really only refer to one of these civilisations, Western Europe, where there is significant historical evidence of a marked decline in scientific, technological, agricultural, economic, educational and literary activities during this period. There was also a considerable decline in the population of Western Europe, notwithstanding migrations of Germanic peoples from northern Europe. Christianity is likely to have been only one of several causes of the Dark Ages.

References

Backman, Clifford R. (2015) The Worlds of Medieval Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bennett, Judith M. (2011) Medieval Europe – A Short History. McGraw- Hill, New York.

Gibbon, Edward (1788). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. 6, Ch. XXXVII.

Tim Harding B.Sc. works as a regulatory consultant to various governments. He is also studying medieval history at Monash University.

Filed under Essays and talks