Michelle Langley, Griffith University

Where did we humans come from?

Some 40 or so years ago, our origins seemed quite straight forward.

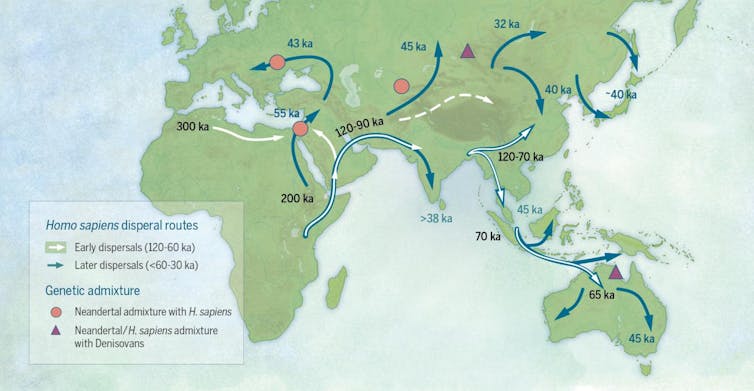

But now we see that the human story is far more complex. As summarised by Christopher Bae and colleagues in their latest paper just published in Science, data from Asia and Australia is becoming vital in piecing this new history together.

Zoom using +/- and click on each site to view more information. The box at top left can also be used to navigate through the evidence.

Read more: Curious Kids: Where did the first person come from?

The original story went something like this: modern humans (Homo sapiens) evolved to their current anatomical form in sub-Saharan Africa sometime after 200,000 years ago. They hung around for a bit, then groups started moving out of the homeland.

Arriving in Western Europe, a “human revolution” soon occurred (40,000 years ago), resulting in our much celebrated artistic and complex language abilities, a sort of creative explosion. These cognitively and technologically advanced peoples then out-competed the indigenous Neanderthals (and other archaic, or relatively ancient, human groups) and ultimately conquered the entire globe.

But fresh evidence has forced a rethink of this version of human history.

Modern humans

New analyses of human fossils have pushed back our earliest recognisable modern ancestors to around 310,000 years. And they weren’t found in eastern or southern Africa (like previous fossil finds), but from a site called Jebel Irhoud in Morocco. These findings have raised questions regarding exactly how – and where – we became “modern”.

Traditionally, we saw the primary difference between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom as being the use of tools. However, primatologists and other biologists have been recording more and more instances of chimpanzees, orangutans, and other creatures making and using tools.

More than that, work initially in southern Africa has demonstrated that the creative explosion didn’t happen in Europe – it happened back in Africa, and far before the original 40,000 years ago date.

Currently, we understand that our complex cognitive and social capacities first began to emerge at around 100,000 years ago or earlier. And it wasn’t even an explosion, but probably more like a slow burn that slowly built into the raging fire of modern creativity.

New and old humans

Perhaps the most intriguing new evidence comes from the analysis of ancient DNA samples.

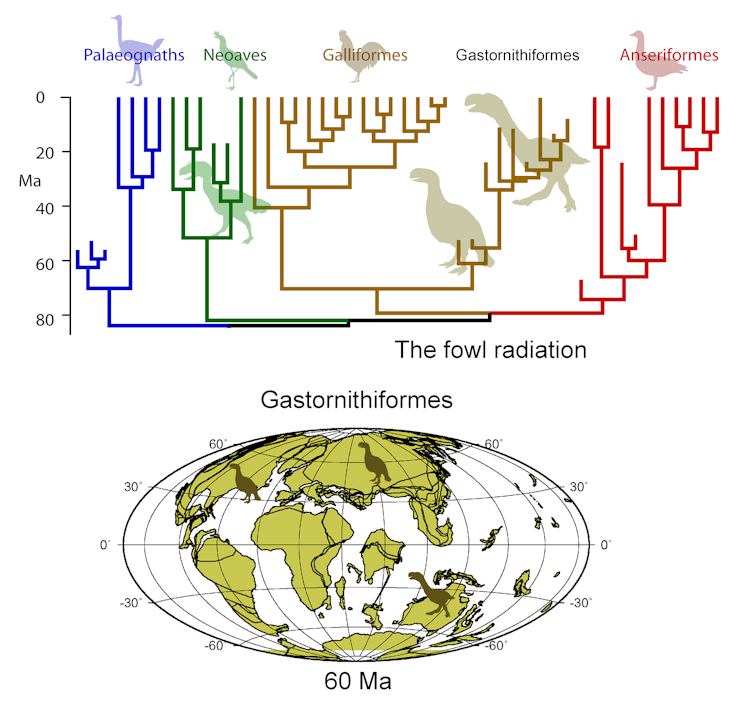

These studies are showing that interactions between the “new” humans (Modern Humans like you and me) and the “old” humans (Neanderthals, Denisovans, Homo erectus, Homo florensiensis, that are all now extinct) was not just a case of simple replacement. Instead, it appears that groups of new and old humans intermingled, interbred, fought, and interacted in a multitude of different ways which we are still disentangling.

Read more: Neanderthals didn’t give us red hair but they certainly changed the way we sleep

The results of these encounters appear to have left some lasting legacies, like the presence of between 1-4% Neanderthal DNA in non-African Modern Humans.

These studies are also beginning to identify some interesting cognitive differences between “us” and “them”, such as the fact that while we modern humans are susceptible to brain conditions like autism and schizophrenia, it appears Neanderthals were not.

The Asian story

The Australasian region is playing a larger and larger role in rewriting the stories of human history.

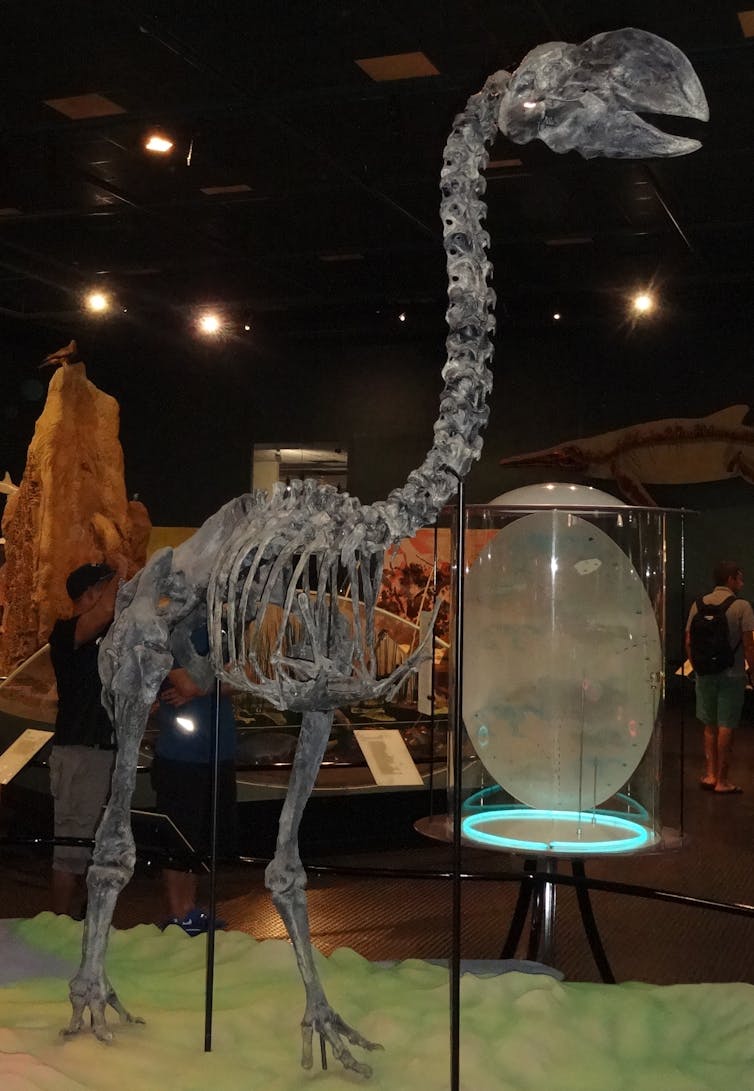

New fossils like Homo floresiensis have completely changed our view of what the human story is in this region. These tiny humans – “the hobbits” – found on the Indonesian island of Flores, continue to challenge palaeoanthropologists – are they a dwarfed Homo erectus? Or are they the descendants of something much more ancient? What are the implications?

But perhaps more interesting (to me at least), are the multitude of artefactual finds which have come to light in recent years.

It now seems that one of the species of older humans, Homo erectus, may have had some capability for symbolism – something rarely associated with them. This hypothesis comes thanks to new analyses of material from old excavations.

Looking back at material excavated from the first known locality of Homo erectus fossils – Trinil on Java, originally discovered by Eugène Dubois in 1891 – scientists stumbled upon a shell exhibiting a zig-zag pattern. This shape had been carefully inscribed using a stone tool more than 400,000 years ago (and perhaps as much as 500,000!). Such geometric motifs had previously been found at southern African sites – but all with Modern Humans – and all significantly younger. In Eurasia too, such designs are present, but rarely seen in Neanderthal contexts.

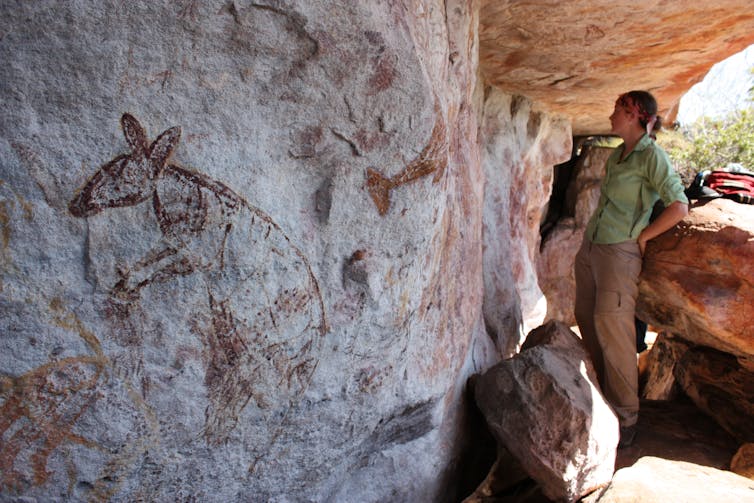

Other findings in Island South East Asia – this time associated with modern humans, Homo sapiens – are showing that the realm of extravagant creativity wasn’t the sole domain of Africa and Europe. New explorations and excavations on Sulawesi and Timor-Leste have recovered not only the oldest rock art in the world, but a vast array of jewellery and other artistic items.

Read more: Ice age art and ‘jewellery’ found in an Indonesian cave reveal an ancient symbolic culture

More than this propensity for art, it has also been found that the first modern human colonists in Asia were practising complex food-targeting strategies, like deep-sea fishing. Such a finding indicates an extensive knowledge of the sea, its dangers, and its rewards.

Focus on Australia

Australia too has been contributing to the rewriting of human histories.

In just the last two years alone, the date of original colonisation of this vast southern continent has been pushed back to around 65,000-years-ago.

The earliest bone ornament in the world, and the earliest ground-edge tool in the world were both found on this continent. It is becoming obvious that Australia was (and is) a land of highly adaptive and innovative people.

The speed at which new and astounding discoveries are being made in Australasia has effectively turned the focus of many human evolution researchers from the old bastions of Africa and Eurasia, much further east.

Recognising the growing importance of this region for furthering our understanding of our story, it is not only individuals that are moving their focus to Asia, but also whole departments. For example, the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution based at Griffith University in Brisbane was launched with the expressed view of focusing on the Australasian region to answer evolutionary questions.

![]() In all, it is an exciting time to be a researcher in this region. Indeed, it appears that the long sought after answers to some of the central questions in human evolution studies may finally be answered here.

In all, it is an exciting time to be a researcher in this region. Indeed, it appears that the long sought after answers to some of the central questions in human evolution studies may finally be answered here.

Michelle Langley, DECRA Research Fellow, Griffith University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. (Reblogged by permission). Read the original article.